Data Migration Is Archaeology - Why Legacy Databases Are Code Repositories in Disguise

3 min read

February 17, 2026

The Illusion of "Raw" Data in Legacy Stacks

A common misconception among operational leadership is that data migration is strictly an infrastructure task—a "lift and shift" of tables from an old server to a modern cloud environment. This view assumes that the database is merely a passive container for information. In modern microservices architectures, this is largely true: the application holds the logic, and the database holds the state.

However, in legacy systems developed 10 to 20+ years ago, this distinction does not exist. In these environments, the database is the application. Through the heavy use of stored procedures, triggers, and user-defined functions, previous developers embedded critical business rules directly into the storage layer.

When you attempt to move this data, you are not just moving records; you are dismantling the engine that makes those records meaningful. This process is less like moving a file cabinet and more like archaeology: you must excavate, catalog, and decipher the function of every artifact before moving it, or the new system will lack the context required to operate.

Stored Procedures - The Invisible Application Layer

The primary vehicle for this hidden logic is the stored procedure. In many legacy ERP or custom operational platforms, stored procedures handle complex tasks such as calculating tax rates, enforcing inventory limits, or triggering compliance checks.

If a migration plan focuses solely on the schema (tables and columns) and the data within them, it leaves this logic behind. The new modern application receives the raw data but lacks the instructions on how to manipulate it. This leads to a scenario where the data is technically present, but the business process is broken.

See "When Stabilizing a Legacy System Costs More Than Replacing It" in our flagship article for how to calculate the cost of reverse-engineering this logic.

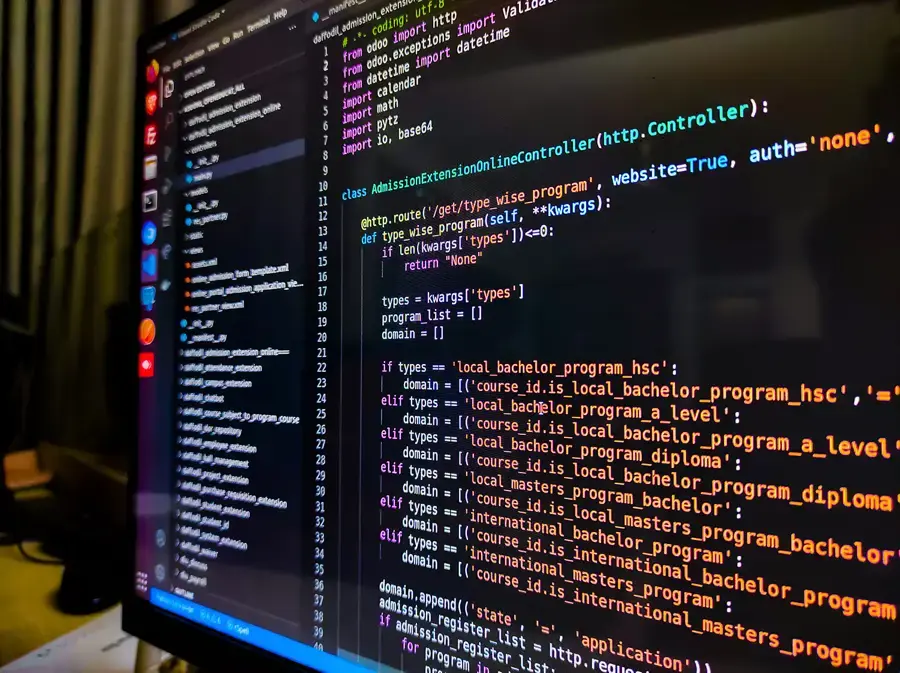

To mitigate this, technical teams must treat the database schema as a code repository. Each stored procedure must be audited to determine if its logic should be rewritten in the new application layer or if it is obsolete. This effectively turns a data migration project into a software development project.

Excavating Implicit Constraints and "Zombie" Logic

Beyond explicit code like stored procedures, legacy databases contain "implicit constraints." These are rules that exist only in the minds of the original developers or are enforced by the legacy application interface, rather than the database itself.

For example, a column labeled STATUS might accept any integer, but the business logic relies on the assumption that the number 99 triggers a specific archival process. If the new system does not account for this unwritten rule, it will treat 99 as just another number, potentially corrupting historical records or failing to trigger necessary downstream workflows.

This "zombie" logic creates significant operational risk during modernization. When data is moved without understanding these implicit dependencies, the new system may function technically but fail operationally. The result is a system that passes unit tests but fails user acceptance testing because it does not behave the way the business "knows" it should.

Conclusion

Treating data migration as a simple transfer of storage is a primary cause of modernization failure. In legacy environments, the database acts as both the hard drive and the processor, holding both the information and the rules for using it.

Successful modernization requires acknowledging that you are not just moving data; you are extracting business logic. By recognizing this early, leadership can allocate the necessary time for the "archaeological" work of decoding these rules, ensuring that the new system inherits the wisdom of the old one without inheriting its technical debt.