Building software that lasts isn’t about moving slower — it’s about making the right decisions early and validating them continuously. Our approach is designed to reduce risk, preserve momentum, and ensure that systems remain adaptable as products evolve.

We focus on structure, clarity, and ownership from the start, so teams aren’t forced into costly corrections later.

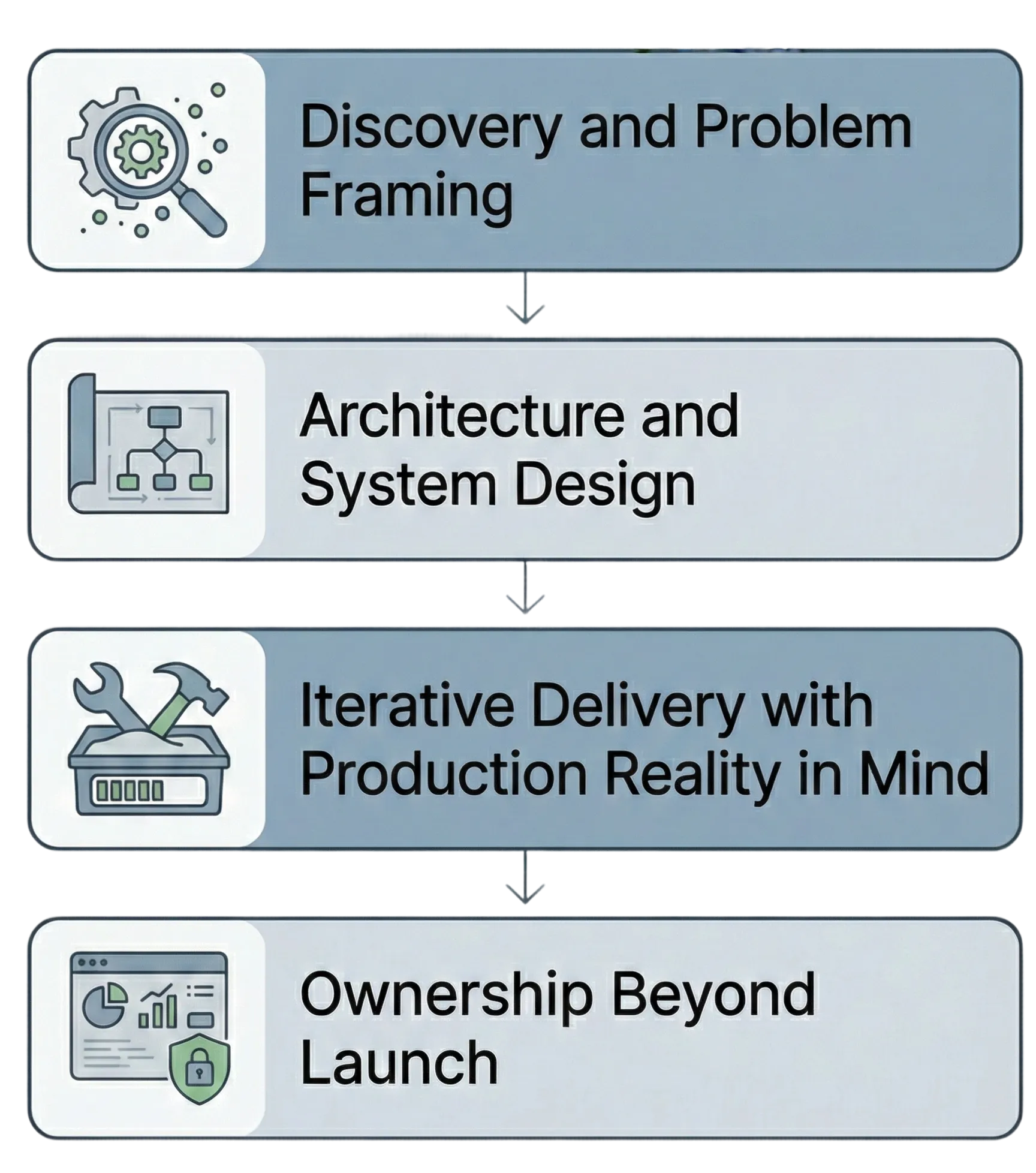

Discovery and Problem Framing

Every successful product begins with a clear understanding of the business it supports.

Before writing code, we work to understand how the product creates value, what constraints it operates under, and where failure would be most costly. This includes clarifying user workflows, technical limitations, regulatory considerations, and organizational realities that shape delivery.

Identifying risk early allows us to make informed tradeoffs and avoid premature builds. Rather than locking in assumptions too quickly, we focus on framing the problem correctly — which is often the most important decision a team makes.

Architecture and System Design

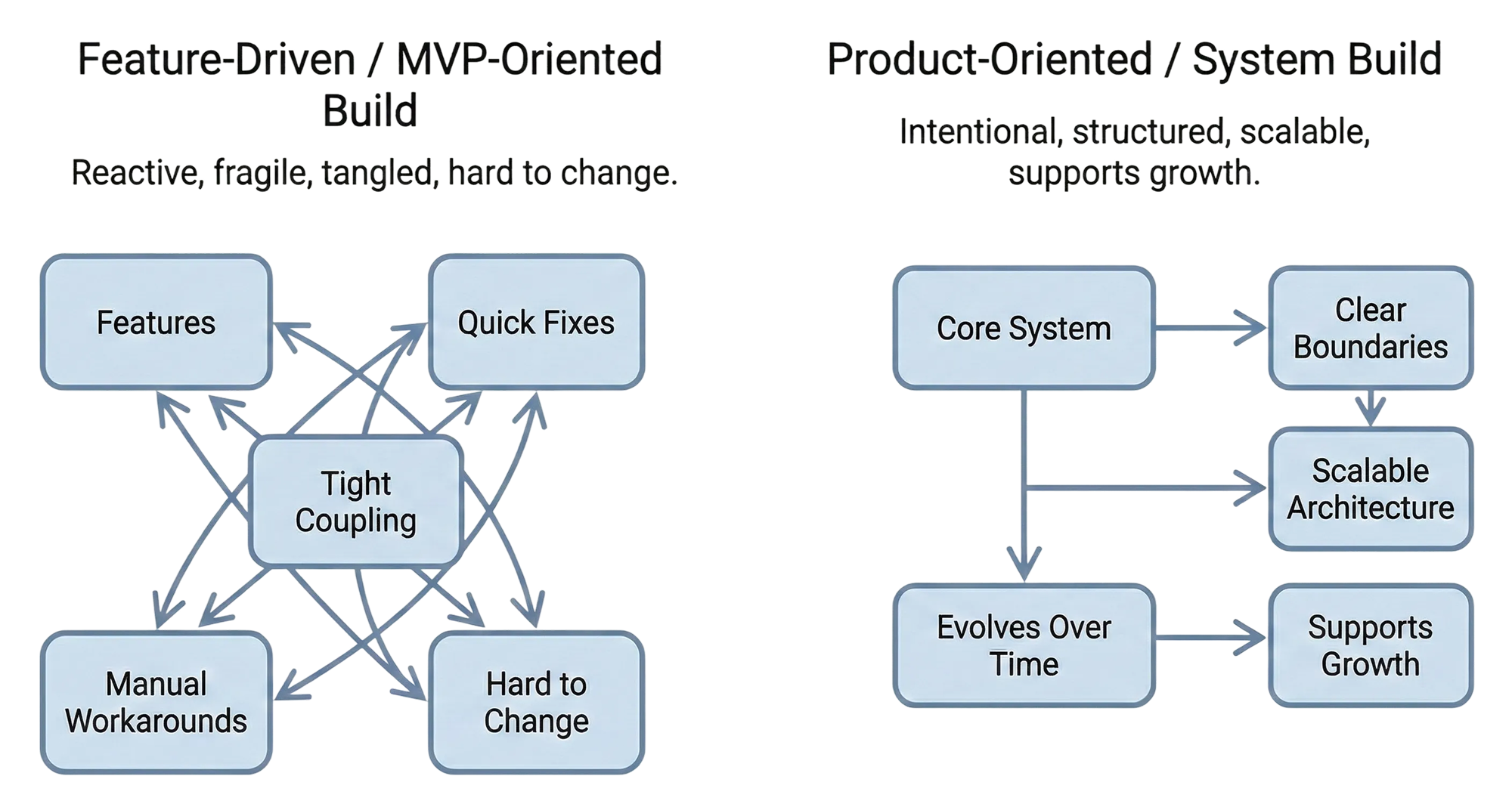

Architecture is where short-term decisions either protect or undermine long-term progress.

We design systems intentionally, choosing structures that support change rather than resist it. This means planning for growth without over-engineering, separating concerns where it matters, and avoiding complexity that doesn’t serve a clear purpose.

Scalability isn’t just about handling more users — it’s about enabling teams to keep shipping confidently as requirements evolve. Good architecture creates leverage over time, instead of accumulating friction.

Iterative Delivery with Production Reality in Mind

We ship incrementally, with the assumption that real-world usage will surface insights no plan can fully predict.

By delivering in stages, we create feedback loops that allow teams to test assumptions, validate direction, and adjust without destabilizing the system. This reduces the risk of large, irreversible decisions and avoids “big bang” launches that concentrate uncertainty.

Production reality matters from day one. Systems are built with observability, testing, and operational stability in mind — not added later as an afterthought.

Ownership Beyond Launch

Launching a product is not the finish line.

Post-launch realities — user behavior, performance under load, evolving requirements — often reveal new constraints. We design with this in mind, distinguishing between ongoing maintenance and intentional evolution.

Ownership means thinking beyond delivery milestones to the long-term health of the product. It’s a mindset that prioritizes sustainability, clarity, and responsibility for outcomes — not just output.

This approach reflects how we build and operate our own software products, where we live with the impact of every technical decision over time.