When Stabilizing a Legacy System Costs More Than Replacing It—And How to Know Before It's Too Late

20 min read

February 12, 2026

TL;DR

The Hidden Mathematics of Legacy Decay

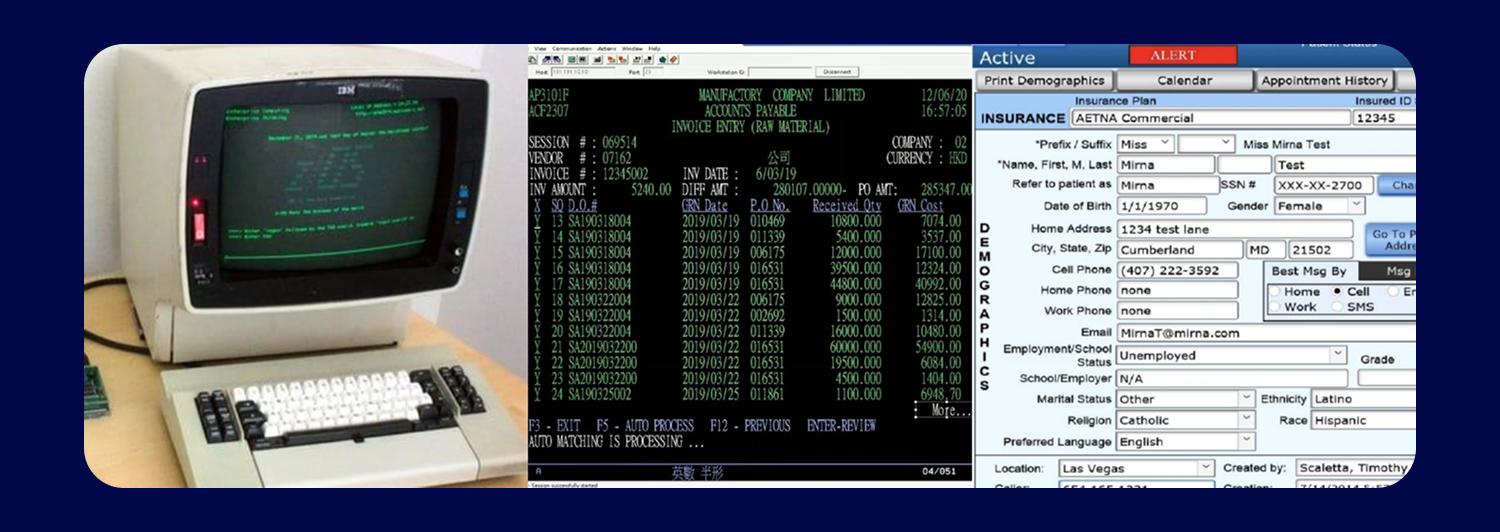

Organizations consistently misjudge the "stabilize vs. replace" inflection point because legacy maintenance costs are hidden across distributed budget lines (OpEx), while modernization appears as a single, large capital decision (CapEx).

This article demonstrates that "stability" in aging systems is often an illusion created by workaround accumulation, not hardening. By the time a legacy system is visibly failing, replacement costs have likely compounded by 40–60% due to complexity accumulation.

This guide provides a 4-step framework to quantify that risk, model the true Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), and execute a modernization strategy before operational paralysis sets in.

Why This Decision Is Invisible Until It's Expensive

Organizations often misinterpret a decrease in incident rates as evidence of system hardening. In practice, this reduction usually creates a "stability illusion," where the operational team has simply learned to navigate around failure modes rather than resolving them.

The system remains fragile, but the triggers are being actively avoided by institutional knowledge that is largely undocumented.

Financial governance naturally favors the familiar risk of incremental maintenance over the shock of modernization. Patching costs manifest as predictable, incremental Operating Expenses (OpEx) that blend into existing run rates.

Conversely, replacement requires a lumpy Capital Expenditure (CapEx) authorization, triggering a level of scrutiny that the "invisible" maintenance burn rate escapes.

This financial comparison is flawed because the true cost of patching is distributed across multiple, disconnected budget lines. Expenses are fragmented into IT labor, compliance audits, manual data workarounds, and opportunity costs from delayed features, meaning they never appear on a single Profit and Loss (P&L) line for executive review.

Patching costs are hidden across multiple budget categories, while replacement costs appear as a single large decision, creating a false perception that patching is lower-risk.

Deferring modernization causes replacement costs to increase non-linearly over time. This escalation is driven by complexity accumulation rather than simple inflation; as data volumes grow and dependency entanglement deepens, the migration path narrows. A project estimated at $120K in Year 1 frequently balloons to $450K by Year 4 due to the exponential effort required to untangle deeply coupled legacy logic.

Leaders often default to "one more year of patching" because the decision to replace feels like an irreversible commitment of capital. However, continued patching is equally irreversible because it consumes the resources required for future adaptation.

By prioritizing short-term stability, organizations effectively foreclose future optionality, locking themselves into a diminishing technical runway.

The Four Indicators That Patching Has Stopped Working

Reliable modernization decisions require objective metrics rather than subjective risk assessments. While incident counts can be artificially suppressed by operational heroism, specific leading indicators predict system failure 12 to 24 months before business operations are visibly impacted. Four objective indicators—MTTR trend, knowledge concentration, change success rate, and compensating control proliferation—signal when a legacy system has become unmaintainable.

Indicator 1 - Mean Time to Resolution (MTTR) Trend

Executive teams should track the trajectory of resolution time rather than the absolute number of incidents. In a decaying architecture, MTTR increases over time even as the team’s experience with the system grows. This counter-intuitive trend occurs because knowledge decay and workaround complexity make every subsequent fix harder to implement safely.

The critical threshold for unmanageability is reached when the MTTR exceeds 4x the historical baseline. For example, an incident type that required 30 minutes to resolve in Year 1 may require 2 to 4 hours in Year 3 due to undocumented dependencies.

When distinct incidents consistently require code archaeology rather than standard troubleshooting, the system is no longer serviceable.

Indicator 2 - Knowledge Concentration Risk

While many organizations assess "bus factor" (sudden unavailability), the "resignation factor" represents a more immediate operational threat. High performers are likely to leave for environments with modern stacks, creating a retention crisis where the last remaining expert holds the organization hostage to legacy logic.

If the salary premium required to retain this individual exceeds 30% above market rates, replacement is often more cost-effective than retention.

Risk is fully realized when knowledge concentration reaches the point where a single individual can resolve incidents but refuses to—or cannot—train others. At this stage, the system is already in failure mode, disguised only by the presence of that specific employee. This dependency creates a single point of failure that no amount of documentation can mitigate.

Indicator 3 - Change Success Rate Degradation

Change success rate measures the percentage of deployments that reach production without requiring a rollback, hotfix, or emergency intervention. Healthy systems typically maintain a success rate between 85% and 95%, whereas fragile legacy environments often degrade to 60-70%. In this state, the cost of testing and remediation begins to exceed the cost of a controlled replacement.

When change success drops below 70%, the metric acts as a hard limit on strategic agility.

If a business unit requests a new product line or feature, the IT response is dictated by the probability of deployment failure rather than technical feasibility. This metric reveals when a system has transitioned from an asset that enables growth to a constraint that protects the status quo.

Indicator 4 - Compensating Control Proliferation

Compensating controls are the manual processes, external spreadsheets, and periodic scripts added to satisfy requirements the legacy system can no longer natively support. Common examples include manual access log reviews, monthly scripts for GDPR compliance, or quarterly data reconciliation between disconnected platforms. These controls represent a "hidden labor tax" distributed across IT, compliance, and operations teams.

The threshold for action is reached when compensating controls consume more than 10% of total operational effort. Unlike software functions, these controls are inherently fragile because they depend on human process adherence.

When MTTR exceeds 4x baseline, change success drops below 70%, knowledge concentrates to one person, or compensating controls exceed 10% of operational effort, replacement becomes more cost-effective than continued patching.

The Compounding Cost of "One More Year"

Postponing modernization is rarely a neutral deferral of expense; it functions more like a high-interest loan with variable rates. In practice, replacement costs do not track inflation. They compound based on system complexity, data gravity, and dependency entanglement, often increasing 40-60% every two years.

The direct cost of maintaining a legacy system typically rises 15-30% annually after it reaches End-of-Life (EOL) status. Vendors aggressively increase support fees to discourage the use of obsolete versions, while the niche expertise required to maintain these stacks commands a premium in a shrinking talent pool. This "maintenance tax" progressively erodes the discretionary budget available for innovation.

Project complexity serves as a multiplier on capital requirements. A replacement initiative estimated at $180K today frequently escalates to $320K within 24 months. This increase is driven by data migration complexity, which scales non-linearly with volume, and by the deprecation of critical third-party integrations that require custom bridging solutions.

Strategic opportunity cost represents the most significant, yet often unquantified, financial impact. Legacy architecture enforces hard constraints on business logic, such as a batch-processing core that precludes real-time dynamic pricing.

These technical limitations directly cap revenue potential, effectively subsidizing competitors who operate on modern, event-driven stacks.

Regulatory risk should be modeled as a specific financial liability rather than a qualitative concern. Executives can calculate the Expected Value of non-compliance by multiplying the probability of an audit by the potential penalty and the likelihood of system failure. This calculation frequently reveals that the status quo carries a higher probabilistic cost than the modernization project itself. Delayed replacement doesn't defer cost—it compounds it.

Why "Stabilization" Becomes Permanent (The Quiet Failure Patterns)

Stabilization often feels like progress because individual tickets are closed successfully and Service Level Agreements (SLAs) are met. However, this creates a dangerous feedback loop where short-term fixes calcify into long-term architectural constraints. These failures are "quiet" because they rarely trigger immediate executive escalation; instead, they manifest as a gradual erosion of capability that only becomes visible in aggregate after 18 to 24 months.

Stabilization fails quietly through patterns like patch accumulation, perceived stability masking adaptability loss, and hidden dependencies creating time bombs. The following patterns illustrate the specific mechanisms by which organizations inadvertently lock themselves into unmaintainable systems.

Pattern 1—Death by a Thousand Patches (Workaround Accumulation)

In this scenario, critical-but-not-catastrophic failures occur on a 3-to-6-month cadence. The engineering team responds with localized workarounds—manual data exports, overnight scripts, or configuration tweaks—that resolve the immediate symptom. Because the incident is closed, the organization perceives the system as functional, yet these workarounds are rarely documented with the same rigor as core code.

Over time, operational tempo slows dramatically as new changes must account for a web of interacting, undocumented constraints. Testing becomes exponentially complex, often extending change windows from hours to days. Strategic agility is effectively lost; when the business requests a new feature, IT cannot provide a crisp timeline because the system is bound by twelve layers of fragile logic.

Pattern 2—The Stability Plateau (Fragility Mistaken for Resilience)

After 12 to 18 months of aggressive patching, incident rates often decrease, creating a "stability plateau." Leadership frequently interprets this silence as a signal that the system has been fixed, leading them to deprioritize replacement discussions. In reality, the system is only stable for the current load, data volume, and user count; it has lost all adaptability.

The fragility is exposed immediately when business conditions change, such as during an acquisition or a traffic spike. Because the team has optimized solely for the status quo, the system fails in ways the current engineers have never encountered. By the time this catastrophic failure occurs, the window for a controlled migration has closed, forcing a replacement in crisis mode at 3-5x the normal cost.

Pattern 3—Hidden Dependency Time Bombs (Deprecated Components)

Many legacy systems rely on vendor components, libraries, or integrations that have been officially deprecated but remain functional. Teams often ignore these warnings because the component "still works," not realizing that deprecated software functions for 12-36 months before failing. During this period, security exposure grows silently as Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs) accumulate without patches.

When a vendor finally disables the component or a security mandate forces its removal, the system breaks without graceful degradation. The migration complexity at this stage explodes because the gap between the legacy component and its modern equivalent has widened significantly. What would have been a standard 6-week migration in Year 1 becomes a high-risk 6-month re-platforming effort in Year 3.

Pattern 4—Compliance Drift Requiring Manual Controls

Legacy systems built before regulations like GDPR, CCPA, or SOC 2 often lack native compliance capabilities. To pass audits, organizations implement compensating controls—manual processes, spreadsheets, or external tools—that satisfy the auditor but do not modernize the underlying architecture. These controls depend entirely on human process adherence.

Quiet stabilization failures include: workaround accumulation increasing operational complexity, stability plateaus masking adaptability loss, deprecated dependencies creating security exposure, and compliance drift requiring permanent manual processes.

The true cost of this compliance drift is hidden in 15-minute increments distributed across multiple staff members, never appearing as a single line item. When the staff member who "owns" a specific manual control departs, the process degrades, leading to inevitable audit failure.

The Three Replacement Paths (And Their Real Failure Modes)

There is no universally superior modernization strategy; every path trades off speed, cost, operational risk, and long-term flexibility. Most modernization failures stem not from choosing the wrong technology, but from a misalignment between the chosen path and the organization's actual execution capacity. Three replacement paths—Lift-and-Shift (rehost), Refactor (strangler fig), and Rebuild (greenfield)—each have distinct cost profiles, timelines, and failure modes that organizations often misunderstand.

Path 1—Lift-and-Shift (Rehost): Fast Infrastructure Change, Slow Value Realization

This approach moves the existing application to cloud infrastructure with minimal code changes. It is appropriate when the system is stable, well-understood, and the primary objective is immediate disaster recovery improvement or data center exit rather than functional enhancement. The realistic timeline for this transition is typically 6 to 12 months.

While upfront costs are the lowest of the three options, ongoing operational costs often exceed projections by 40-70%. This variance occurs because monolithic legacy architectures cannot leverage cloud-native features like auto-scaling or managed services, effectively porting technical debt to a more expensive rental model. Organizations should choose this path only if the goal is strictly infrastructure modernization, as it freezes application logic in its current state.

Path 2—Refactor (Strangler Fig): Lowest Risk, Longest Timeline

Refactoring involves incrementally replacing legacy functionality with new services while the old system continues to run. Over a period of 24 to 48 months, new code "strangles" the legacy system until the old codebase can be decommissioned. This path offers the lowest risk profile because it spreads the cost over multiple budget cycles and avoids a "big bang" cutover.

The primary risk in this approach is the "permanent intermediate state." Without rigorous architectural discipline, the integration layer built to connect the old and new systems can calcify into a permanent third system that requires its own maintenance. This path is optimal when business continuity is paramount and the organization can sustain a multi-year program without losing executive focus.

Path 3—Rebuild (Greenfield): Clean Break, Highest Execution Risk

A greenfield rebuild involves creating a new system from scratch while running the old system in parallel until a final cutover. This path is necessary when legacy logic is so entangled that the effort to refactor would exceed the cost of rebuilding. While it promises the lowest long-term technical debt, it carries the highest execution risk.

Timelines for rebuilds frequently extend 50-100% beyond initial estimates due to scope creep and the discovery of undocumented requirements.

The most significant hidden cost is the parallel run period, which requires the organization to maintain two distinct systems, reconcile data discrepancies daily, and train staff on both platforms simultaneously. Lift-and-Shift is fast but often increases costs; Refactor has the lowest risk but the longest timeline and can create permanent dual systems; Rebuild provides a clean break but timelines typically double and scope creeps.

Building the Business Case Finance Will Approve

To secure funding for modernization, IT leaders must present a financial model that accurately reflects the compounding costs of the status quo. Most executives underestimate the true cost of continued patching while overestimating the risk-adjusted cost of replacement. A rigorous 5-year Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) analysis narrows this perceived gap by exposing the "invisible" budget lines that legacy systems consume.

Soft costs must be quantified in terms that finance teams accept: expected value of risk, opportunity cost of delayed features, and the labor burden of compensating controls. Leadership needs to see not just the immediate project cost, but the downstream financial consequences of each decision path—including the decision to do nothing.

A 5-year TCO model comparing patching, immediate replacement, and delayed replacement—with quantified soft costs like knowledge risk, opportunity cost, and regulatory exposure—makes replacement financially defensible.

The 5-Year TCO Framework (Three-Column Comparison)

A defensible business case compares three specific scenarios side-by-side.

Column 1 (Continue Patching) aggregates vendor support contracts, internal labor, compensating controls, incident response, and the escalating retention premiums for key personnel. This baseline rarely remains flat; it typically increases 5-10% annually as system fragility grows.

Column 2 (Replace Now) includes migration costs, new platform licensing, training, parallel run expenses, and a risk mitigation buffer (typically 20-30%).

Column 3 (Replace in 2 Years) captures the "hidden default" choice: it includes two years of Column 1 costs plus the costs from Column 2, adjusted for a 30-50% complexity inflation factor. Most organizations discover that Column 3 is objectively the most expensive option, yet it remains the path of least resistance when "stabilize vs. replace" decisions are deferred.

Quantifying Soft Costs Finance Will Accept

"Soft costs" are often dismissed as speculative, but they can be converted into hard numbers using actuarial methods. Knowledge concentration risk should be calculated as the full replacement cost of a key expert: recruiting fees + onboarding time + 6 months of productivity ramp + the operational impact of a 6-month gap. For a senior engineer on a legacy stack, this figure frequently exceeds $300,000 to $500,000.

Strategic opportunity cost is quantified by estimating the revenue or margin impact of features that the legacy system actively prevents, such as real-time inventory lookups or mobile-first customer portals. Similarly, regulatory risk can be modeled as an expected value: the probability of an audit multiplied by the potential penalty and the likelihood of non-compliance. These are not IT assertions; they are standard risk calculations that CFOs use for insurance and investment decisions.

De-Risking the Approval (What Leadership Needs to Hear)

Executives are more likely to approve modernization when the proposal acknowledges uncertainty. Present three scenarios—best case, realistic case, and worst case—along with specific mitigation plans for the worst-case outcomes. This demonstrates that the team is managing risk, not just hoping for success.

Rather than requesting a full budget authorization upfront, request funding for Phase 1 (discovery and architecture) to provide a concrete Phase 2 estimate within 90 days. Finally, frame inaction as an active choice with consequences: "If we do not proceed, we will be forced to make these three specific trade-offs in 12-18 months." Executives approve replacement when soft costs (knowledge risk, opportunity cost, regulatory exposure) are quantified as expected value, and when inaction is framed as a decision with measurable consequences.

The Failure Modes No One Warns You About (And How to Avoid Them)

Modernization efforts rarely fail due to fundamental technology choices; they fail because operational risks are treated as implementation details rather than structural threats. These failure modes are not edge cases but high-probability events that occur when governance focuses solely on "getting to code complete." Most of these failures are preventable, provided they are engineered out of the project plan before the first line of code is written.

Underestimating Data Migration Complexity

Data migration is almost never a simple Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) exercise. It frequently exposes that the legacy system has been silently tolerating or correcting bad data for years through hidden scripts and manual interventions. When these undocumented business rules are stripped away during migration, data quality issues manifest as critical system failures.

Teams often discover referential integrity gaps and format mismatches only after the new system rejects the imported data. To mitigate this, organizations should allocate 30-40% of the project timeline specifically to data analysis and cleanup. Treat migration as a distinct workstream requiring its own quality assurance phase, rather than a final task to be rushed before go-live.

Declaring Success at "Code Complete" Instead of "Operationally Resilient"

There is a dangerous gap between a system that functions in User Acceptance Testing (UAT) and one that is supportable in production. Post-launch instability often stems from the lack of operational tooling—runbooks, monitoring dashboards, and escalation paths—rather than bugs in the core software.

True success requires validating the "operational readiness" checklist, including disaster recovery plans tested under live-fire conditions. Leaders should define rigorous "production ready" criteria in the project charter and link final vendor payments to a 30-day operational warranty period. This ensures the team remains engaged until the system is stable, not just deployed.

No Rollback Plan for Cutover (The Point of No Return)

Most cutover plans optimize for success, failing to account for the "partial failure" scenario where a migration stalls at 60% completion. Without a pre-tested rollback strategy, the team is forced to "fix forward" under crisis conditions because reversing the process is no longer technically possible. This is the point where technical issues become business continuity disasters.

A viable mitigation strategy defines clear rollback criteria before the maintenance window opens. The rollback procedure must be tested in a staging environment and designed to execute within 50% of the planned cutover window. If the team cannot guarantee a clean reversal, the risk of proceeding is mathematically unacceptable.

Ignoring Interdependent Systems (The Cascade Failure Risk)

Legacy environments are rarely isolated applications; they are accidental "systems-of-systems" connected by fragile batch files, shared database tables, and manual file transfers. Modernizing a core component without fully mapping these dependencies inevitably causes silent failures in adjacent systems that may not be discovered for weeks.

Preventable failures: allocate 30-40% of timeline to data migration, define operational readiness before go-live, test rollback procedures, and map system dependencies before starting. Mitigation requires a dedicated 2-to-4-week discovery phase combining automated network traffic analysis with stakeholder interviews to identify these invisible tethers.

Common modernization failure modes include underestimating data migration, declaring success too early, lacking rollback plans, and ignoring system interdependencies—all preventable with structured mitigation.

Mid-Flight Course Corrections (When You're Already on the Wrong Path)

Recognizing a modernization project is off-track at the 12-month mark of a 24-month timeline is a severe leadership test, yet pivoting is invariably cheaper than completing a flawed architecture.

The decision to intervene must be driven by objective data—specifically timeline variance, cost acceleration, and the ratio of delivered functionality to resource burn—rather than optimism or emotional investment. Mid-flight course corrections: if Lift-and-Shift costs are spiraling, refactor expensive components first; if Rebuild timelines double, freeze scope and launch MVP; if Refactor creates permanent dual systems, set hard decommission dates.

You Chose Lift-and-Shift and Cloud Costs Are Spiraling

When a Lift-and-Shift migration results in spiraling cloud costs, the root cause is typically treating the cloud as a rented data center rather than a managed platform. The most effective recovery is not to revert to on-premises hosting, but to aggressively refactor the top 20% of components that drive 80% of the invoice. A focused 6-to-12-month sprint to optimize database layers and compute-intensive jobs can capture the majority of potential savings without requiring a full system rewrite.

You Chose Rebuild and Timeline Has Doubled

If a Rebuild initiative sees its timeline double, the primary culprit is often unchecked scope creep disguised as "feature parity" requirements. The necessary correction is an immediate scope freeze, targeting a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) release with 70% of the planned functionality. If the timeline has tripled while delivered functionality remains under 40%, the organization must confront the sunk cost fallacy and evaluate whether transitioning to a Strangler Fig pattern is a more viable path to completion.

You Chose Refactor and the "Strangler" Is Becoming a Permanent Hybrid

A Refactor strategy fails when the temporary integration layer evolves into a permanent third system with its own dedicated support team. To break this paralysis, leadership must set a hard, non-negotiable decommission date for the legacy system and work backward to prioritize the remaining migration tasks. Often, the only way to salvage a stalled Strangler migration is to sacrifice low-value legacy features entirely rather than spending months replicating them in the new architecture.

How to Use This Framework (Decision Workflow for Directors)

This framework is designed for directors who must deliver a recommendation to executive leadership within a 30-to-60-day window. It structures the analysis to produce a defensible decision memo rather than a premature Request for Proposal (RFP). By following this four-step workflow, leaders can assess their current state, model financial options, and select a modernization path based on objective risk tolerance.

Decision workflow: (1) score current state using four indicators, (2) model 5-year TCO for patch vs. replace, (3) select modernization path based on risk tolerance, (4) define success criteria beyond go-live.

Step 1—Assess Current State Using the Four Indicators

The first step is to score the system against the four key indicators: MTTR trend, knowledge concentration, change success rate, and compensating control proliferation.

Directors can derive these scores from existing data sources such as incident logs, deployment reports, and compliance audit documentation. If two or more indicators fall into the "red zone," the data supports a recommendation that replacement is now more cost-effective than continued patching. This assessment typically requires 1-2 weeks to complete.

Step 2—Model TCO for Patch vs. Replace Over 5 Years

Next, build a three-column financial model comparing "Continue Patching," "Replace Now," and "Replace in 2 Years." Honesty regarding hidden costs is critical; the model must include labor for manual workarounds, the burden of compensating controls, and the escalating retention premiums for key personnel. Additionally, include strategic opportunity cost—the estimated revenue impact of features the current system cannot support.

This 2-3 week exercise produces the financial justification finance teams require.

Step 3—Select Modernization Path Based on Risk Tolerance and Timeline

With the financial case established, select the modernization path that aligns with organizational constraints. If risk tolerance is low and timelines can be extended, the Strangler Fig Refactor is the optimal choice. If urgency is high and the system is well-understood, Lift-and-Shift with a subsequent refactoring roadmap may be necessary. For organizations requiring a clean break with secured executive sponsorship, a Rebuild is appropriate.

This step, taking roughly 1 week, focuses on explicitly documenting the trade-offs of the chosen path.

Step 4—Define Success Criteria Beyond "Go-Live"

Finally, define success criteria that extend beyond the initial deployment. Operational readiness metrics should include the existence of runbooks, instrumented monitoring, and documented escalation paths. Business outcomes must be measured in improved feature velocity, reduced incident rates, and TCO reduction. True success is not defined by the deployment of the new system, but by the decommissioning of the old one.

Four-step workflow: assess using indicators (1-2 weeks), model TCO (2-3 weeks), select path based on risk tolerance (1 week), define operational success criteria (1 week)—produces defensible recommendation in 5-7 weeks.

Key Takeaways

The Stability Illusion: A decrease in incident rates often signals that teams have learned to avoid failure modes, not that the system is fixed. If MTTR is rising while incident counts fall, the system is becoming unmanageable.

The Four Indicators of Rot: Move beyond subjective risk assessments. Initiate replacement when:

MTTR Trend exceeds 4x the historical baseline.

Change Success Rate drops below 70%.

Knowledge Concentration means a single engineer’s departure creates immediate operational risk.

Compensating Controls (manual workarounds) consume >10% of operational effort.

Cost of Delay is Non-Linear: Deferring replacement does not save money; it acts as a high-interest loan. Replacement costs typically increase 40–60% every two years due to data gravity, dependency entanglement, and the "maintenance tax" of legacy support.

Choose the Path by Risk, Not Tech:

Lift-and-Shift: Fast infrastructure exit, but often raises OpEx.

Refactor (Strangler Fig): Lowest risk, but requires multi-year discipline to avoid creating a permanent hybrid mess.

Rebuild: Cleanest break, but highest risk of scope creep and timeline failure.

Success = Decommissioning: A modernization project is not complete when the new system goes live; it is complete only when the legacy system is turned off. Define success by the removal of the old, not just the addition of the new.